I don’t usually like the idea of leaving somewhere less perfect than I found it, but as I picked a small piece of coral off the white sand beneath my feet, I got so caught up in the remoteness and exclusivity of this uninhabited island in the South Pacific ocean that I felt as though I needed to bring back something to remember it by. Monuriki, part of a group of islands known as the Mamanucas in Fiji’s Western stretches, lends itself to the role of a traditional desert island. Visually appealing but mysteriously intimidating, with an ominous island breeze that no one ever hears whistling over the sway of coconut trees that no one will ever eat from.

From back home in the UK it took 3 flights averaging about 10 hours each, and 2 boats of varying sizes to get here.

Fiji is one of the few places I’ve been to where reality has matched expectations, I’d always dreamed of far-away islands that were as hard to leave as they were to get to, where people were sparse and sunsets could define a lifetime. Growing up, the South Pacific always represented my best chance of a Robinson Crusoe style abandonment on a desert island, the ultimate form of escapism for a teenager navigating London’s urban jungle. It was more than just palm trees and sand, we saw those in the summer holidays. It was strange creatures, new cultures and year round tropical temperatures with a smattering of fierce, humid thunderstorms.

On arrival at Nadi (pronounced Nandi) airport on Fiji’s biggest and central island, Viti Levu – a mainland of sorts, it was clear from the start that this was the kind of place I’d imagined. Misty green mountains in the distance dotted with vegetation, colourful flowers and other strange and exotic plants I’d never seen before growing from every corner. As I tried to get my head around this novel landscape a rainbow appeared through the dense humidity to round off my first impressions.

And this was just the airport car park.

I was immediately addicted and wanted to explore further reaches of this unique landscape. Monuriki, nicknamed Castaway as it was the setting for the 2000 film of the same name, is not to be confused with the larger, inhabited island known as Qalito which is also nicknamed Castaway, and also part of the Mamanuca Islands. Confusing? It was to start with. But booking a tour through Seaspray, a local travel company, simplified things as they make it clear in their itinerary that they’ll be taking you to the island shown in the film.

The tour itself would take us on a day trip to two Fijian islands. On our way to the aforementioned Monuriki we would be supplied with complimentary champagne and an on-board buffet before heading off to Yanuya, a slightly larger island with locals we’d get to mix with and who’d invite us to take part in a celebrated South Pacific ritual – the Kava ceremony.

Like most other tours I’ve done in Asia and the Pacific it was surprisingly well organised. This despite a problem on (Google maps’ part) showing the pickup point – Ramada Hotel in Wailoaloa Bay – in the wrong location. I discovered it was actually only about 20 metres away from Bamboo Travellers, the brilliantly well-run beach bar/hostel where I was staying. The previous day in a bid to prepare myself I’d taken a practice-run where I followed Google’s faulty co-ordinates and ended up going on a 3 mile walk in totally the wrong direction, dodging stray chickens from peoples front gardens along Nadi’s main highway, the looming Sleeping Giant mountain in the distance my only other reference point. Definitely the scenic route, but all this to ease my nerves over what would eventually be a 20 metre walk? In this hidden corner of the world even big companies like Google forget to check whether they’ve got everything right.

Pickup the next day was thankfully less complicated and on arrival at Nadi port, I was able to check the the marina timetables and match them up to our itinerary – the staff there were more than happy to guide people in the right direction once you handed your booking confirmation to them and as usual, finding the right boat is always so much less complicated than you think it will be. The first boarding was a large catamaran, where people from various other tours as well as those separately travelling to resorts further out were taken on this island hopping route up the Mamanucas. Think getting the train out to the suburbs, if the train was a boat and the suburbs, instead of taking you further away from the city centre, were South Pacific islands, each feeling more remote than the last.

Weaving through just a small number of Fiji’s many islands, there was a combination of uninhabited ones covered in swaying forest and more hospitable ones which were home to small communities. Those of us on the Seaspray Day Adventure tour met the guides on a smaller boat off Mana Island, one of the inhabited ones (so much so that it even has a small airport) and started our journey towards Monuriki. On a map, the distance between these two points doesn’t seem great and I’m usually fine on boats. However with the combination of free alcohol, 2 hours of glaring sun, and choppier waves due to an (understandably) slower speed than the catamaran, even I started to feel a bit seasick.

Despite the journey feeling like it took way longer than it actually did, we were given a good amount of food to distract us and the tourguides were friendly and informative throughout, getting their guitars out and having a singalong, and in general giving everyone a good laugh while we were out being slowly cooked by the heat.

The film Castaway depicts a man stranded alone on a desert island for 4 years after a plane crash, coming to terms with leaving loved ones behind and learning to fend for himself in a harsh natural environment, and although I knew I was on a boat out of there in about an hour and a half, I could definitely see why Monuriki was chosen as the setting for such a film. It is a beautiful place to experience but totally unlivable for an extended period of time, with volcanic rocks covered by forest and reaching 178m high taking up most of the island and a few small beaches the only places of open space. The two nearest islands are a bit of a swim away and also have a population totalling zero.

Though I knew they existed I’d never seen forests like the ones on Monuriki, growing exclusively out of sand it seemed. On touchdown, despite feeling slightly intimidated by my surroundings they managed to grab my full attention. The footpath I followed in my eagerness to explore led away from the safety of the beach and into the increasingly dense woodland, it was lined with fallen pandan branches and shavings of bark which the strong winds had seen to over time. The same wind that was making the branches of every palm tree in sight flutter in the same direction simultaneously like the waving arms of party people at a music festival. I imagined exploring the forests further up where the rocky terrain was inaccesible would have been its own journey.

On my way I encountered many of what I believed to be something similar to the sweet gum balls that you find in other parts of the world – pretty much tiny spiky balls – which had fallen off from the trees and were hidden in the sand and more than prepared to give you a shock if you stepped on one of them too hard (which I did). If you want to go for a wander, a pair of sandals will be your best friend.

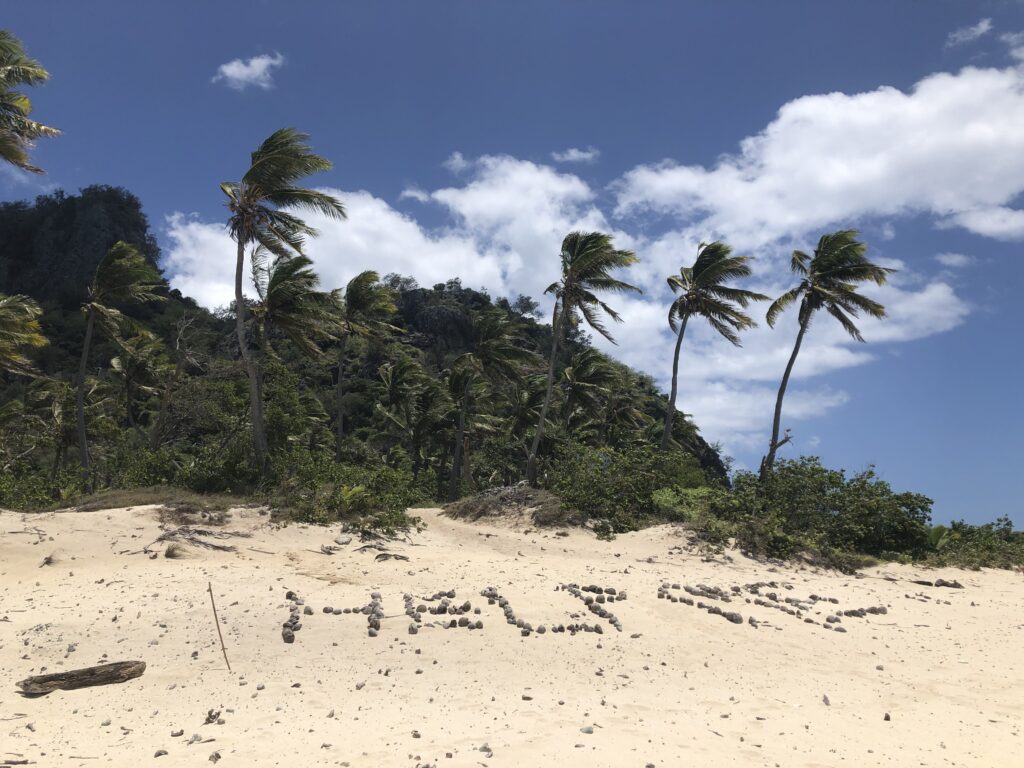

Another thing that you’ll find a lot of on Monuriki is coconut trees. Empty coconut shells are everywhere and round the corner from where we were dropped off have even been used to create a very instagrammable spot, someone having spelled out “help me” in the sand with them. Scrolling through the Monuriki-tagged images before and after my trip, it would appear that this is a permanent fixture there and although the message written out in the film is a bit different, it was just a bit of fun and worth me spending a good 20 minutes trying to get the perfect picture with.

You can snorkel too, the waters in this area are known as perfect places to get your goggles on and the tourguides gave everyone their own snorkel and flippers before we got there. Since I hadn’t done so for a while, I didn’t have the confidence to go as far from the shore as I could have so missed the chance to swim through colourful coral and look out for sea turtles. The best I could manage was about five metres out from the beach where the only thing I saw when I dipped my head in were thick swirls of sand around me. Somehow, relaxing on the beach after my walk was good enough for me.

After an hour or two of exploring and taking it all in, a shout came out for us to get back onto our boat to head to our next destination and at this point I did wonder how my life would have turned out if I’d not heard the call and been left behind. Years of learning how to catch fish and hoping that a big cruise ship would pass by and spot me? What would be the best type of tree to make a raft out of? Do I even want to leave? Luckily our next stop would be to Yanuya Island, a place with at least some population to speak of, just in case things didn’t go to plan.

Fiji’s 300+ islands are almost impossible to compare to one another as they come under so many different headings. They span those untouched by daily human life such as Monuriki, all the way through to party islands with beach clubs that wouldn’t look out of place in Ibiza (see Malamala Island). There are also many similar to Yanuna. Categorising it as “in between” the two is easy but hard to justify.

The traditional Fijian village where most of its population live had its own friendly charm and the locals were happy to welcome visitors. The sight of fruit trees sustaining island life remided me a lot of images I’d seen of the Carribean, and back on the mainland I did notice many cultural similarities, a love for reggae being one. But you won’t see much cricket being played here. Instead of the sound of bat on ball, the school in Yanuya village was host to a full-size rugby field where different groups of children played individual matches within their own little segments. I’d already realised that rugby was by far Fiji’s national sport but was surprised to witness the extent to which it finds its way to all corners.

Not all children were playing rugby though. Some were in lessons, others were helping the adults with their daily work, and some greeted us as we arrived on their shores, posing for pictures as we walked through the village to take part in a kava ceremony, an important tradition in many Pacific communities. Kava, a drink slightly resembling muddy water and having a bitter taste with a hint of liquorice, is made from the peppery Kava plant found throughout much of the continent and with its numbing and mellowing effect is often used to welcome visitors to social gatherings. In a Kava ceremony, the host (often the chief of the village) will give a prayer blessing before dipping a cup into the main bowl (tanoa), taking a sip and handing the cup around the room. There are two options with regard to portion size – “high tide” – a full cup, and “low tide” – a half, and custom dictates that you must drink it in one go.

The chief who welcomed us was a slightly fearsome looking older gentleman with flowing grey hair and a stony face that demanded respect for the ritual he was letting us witness. His helpers gathered intently around him and he had a number of what I assumed were other senior figures from the village set up the room before he recited his own blessing to start the ceremony.

I had actually taken part in a smaller-scale kava ceremony the previous day in Navala Village that wasn’t part of a tour, where my only understanding of what to expect came from the blurry recollections of an Italian air steward who had talked a taxi driver into taking us on the 2 hour drive deep into the Fijian countryside.

I was excited to blindly throw myself into it not knowing what would come next, and as we watched the hypnotising jolts of the chief blessing the room and the drumming of villagers sat around the tanoa in Yanuya I felt priviliged to have at least some idea of what to expect. I’d already decided to just watch from the sidelines rather than take any more sips as I wanted the original memory to feel more meaningful. But when you’re already out in a village like Yanuya, far from an already-remote mainland and taking part in the type of ritual that you’d be lucky to even see on TV, it really doesn’t make a massive amount of difference whether you do it as part of a tour or not. Either way, you’ll be remembering it for a while.

As our day came to a close, I hoped that our hosts on the island would also remember us for a while. And if it wasn’t for my reliability our tourguide would certainly not have forgotten my face in a hurry. Climbing over the rocks on the shore to get back on our boat, he passed me his phone to hold while he needed both hands to help people on. A new iphone, just like you’d get anywhere else in the world. With access to every bustling corner of the globe and presumably the same faulty map that I had on mine (I still haven’t forgiven Google).

With all of us on board, finally motoring away and Yanuya starting to fade into a happy memory, a horrified look filled his face as he realised he’d forgotten something. “Who has my phone!?”. His level of panic was matched by the relief of realising that I had it safely in my pocket, ready to hand back. Scattered around Fiji there are plenty of these remote outposts where if something doesn’t come back with you, it doesn’t come back at all. The more you experience these kinds of places, the more you realise that this only really applies to material possessions – from iphones, to the coral that made the 17,000km trip back home with me. The memories you make don’t need to be kept safe in a back pocket, you don’t need to have a look under the bed for them before you check out of your hostel, and you don’t need to remember to get them back on your boat before it sets off. They’ll stay with you for a lifetime, regardless.